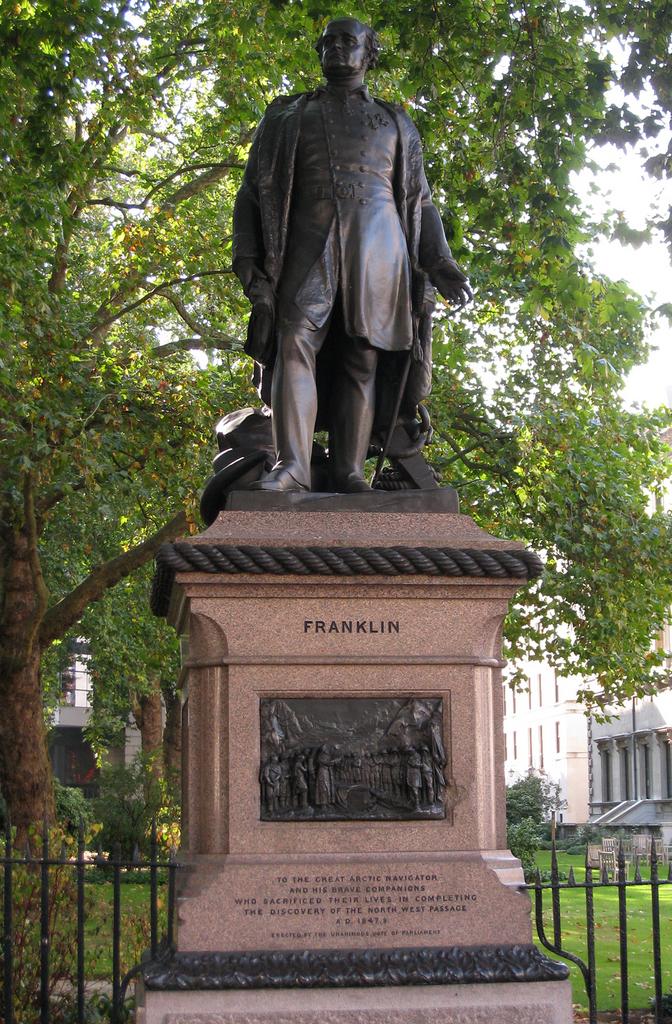

A brief stroll across St James’s Park in London delivers you to Waterloo Place, where you are met by the statues of two tragic Polar figures: John Franklin, Byronic in stature and with an expression of fortitude; and Scott of the Antarctic, dressed in expedition clothes, gazing heroically into the distance. The actual bodies of both men are committed for eternity to the ice they so valiantly attempted to conquer.

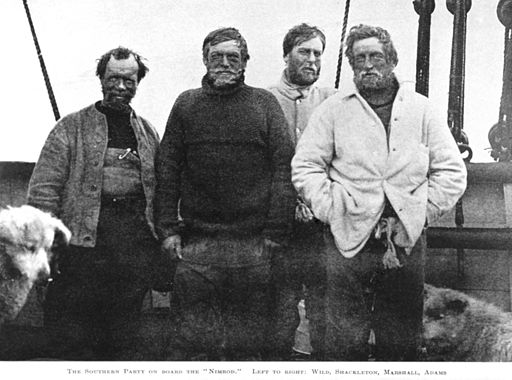

A bronze memorial of another Polar legend, Ernest Shackleton, stands in a recess on the Royal Geographical Society building in South Kensington. At the unveiling of the statue, speeches were made honouring Shackleton; the “noble” statue would remind passers-by of a man “to whom adventure was an inspiration, danger and incentive”, and who was “imbued with the true spirit of Polar exploration”.

These three statues perfectly demonstrate our admiration for those Polar explorers, who are mythologised as martyrs of exploration, willing to endure the worst conditions of Mother Nature and be met by unimaginable suffering, not for love nor money, but in the name of discovery. The gripping stories of these men make up the greatest chapter in the chronicles of human exploration. The poignant details – Captain Scott’s last notes, Shackleton’s fourth man or the cannibals of Franklin’s expedition – have captured and held the public imagination.

But these three gentlemen were in effect admirable failures who, cruelly treated by fate, were unsuccessful in fulfilling their deepest ambitions. Polar history is full of extraordinary accomplishment, from the voyages of James Clark Ross to Fridtjof Nansen’s crossing of Greenland – why, then, are we so drawn to the stories of those who did not succeed?

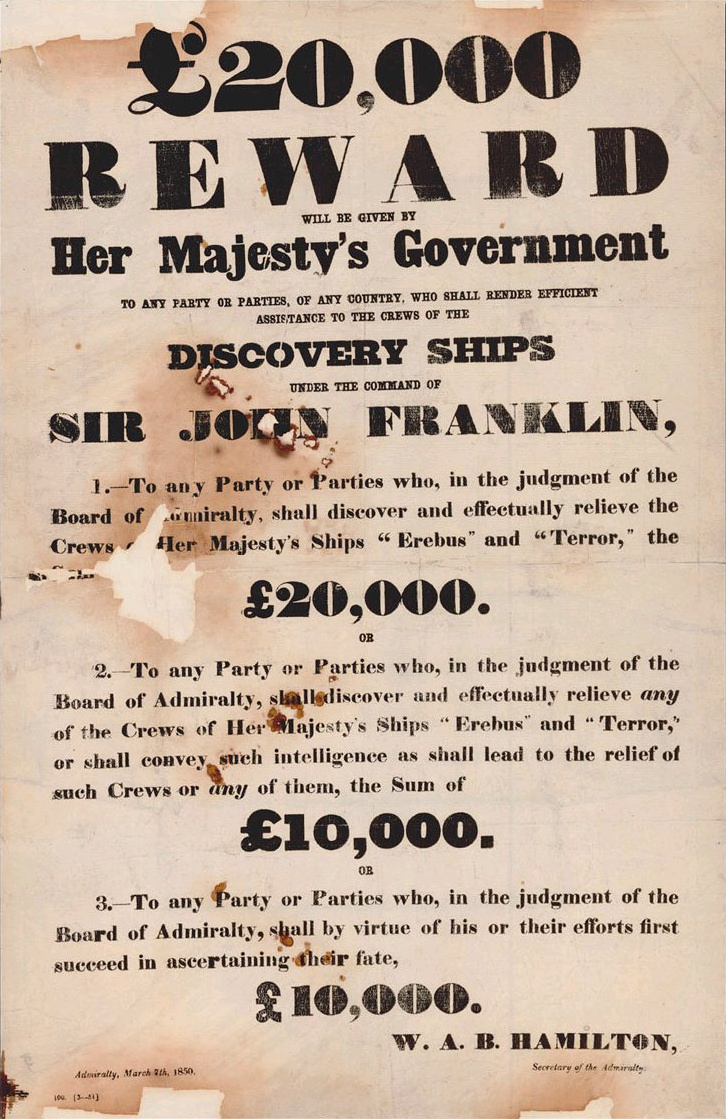

The answer lies in the greatest mystery of the infamous Northwest Passage, John Franklin’s fated expedition. Franklin was no stranger to the horrors of Polar exploration when, in 1845 and in his late fifties, he took command of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, for an ambitious scientific expedition to the American Arctic. Franklin and the crew of 130 men disappeared into the Northwest Passage, never to escape. The mystery of their fate, along with a generous £20,000 reward offered for locating them, inspired countless rescue expeditions to try to discover the fate of his expedition – so many, in fact, that more lives were lost in rescue attempts than on the original expedition.

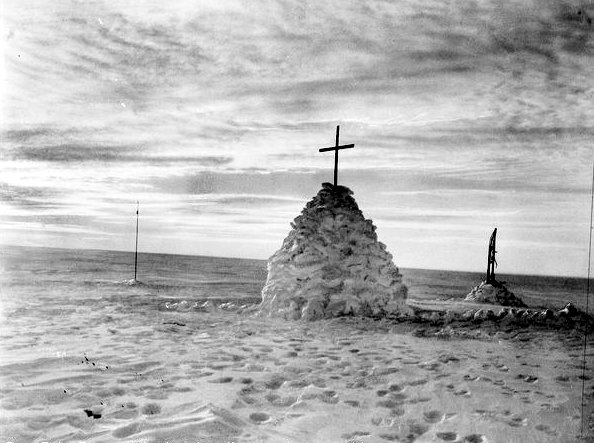

This fanned the flames of the world’s imagination and fixation on Franklin’s lost expedition grew. What had become of the great Polar explorer? Had he discovered the Northwest Passage or some other great Arctic secret? Franklin’s story became mythologised: a heroic Hercules at the bitter and twisted end of life, leading his expedition across the ice in the name of science. Great memorials were erected across the nation as almost shrine to the pursuit of knowledge and science.

The true fate of Franklin was far from the heroic picture imagined by a fascinated public. He died on 11 June 1847, spared the subsequent horror of his fellow crewman – one by one the expedition succumbed to exposure, scurvy and starvation (leading the survivors to resort to cannibalism), and all were most probably suffering from the effects of lead poisoning from the ships’ supplies of tinned food. However, forceful supporters back home – such as Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane, and Charles Dickens – helped cement the image of tragic heroes. Reports from Inuits of cannibalism and ungentlemanly acts were shunned as fanciful and absurd. The mythologization of the expedition was sealed.

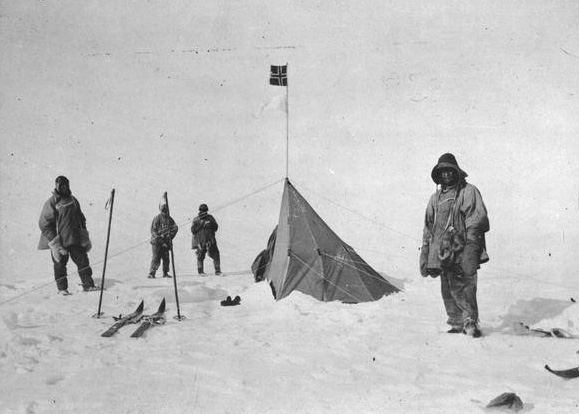

60 years after Franklin’s disappearance, a new Polar fever consumed the world, as the great race to the South Pole began. Captain Scott perfectly captured the Edwardian spirit of the early 1910s, a man of science and gentlemanly morals. He was the antithesis of his Norwegian competitor, Roald Amundsen (a man so hell-bent on being the first to the Pole he was willing to consume his own local dogs to do so – he wrote, “We had agreed to shrink from nothing in order to reach our goal.”) When Scott and his sledding party succumbed to the bitter conditions of the White Continent, a legend was born. He was christened ‘Scott of the Antarctic’ and his journal, plucked from his frozen hands, tells a tale of self-sacrifice, disappointment and misery. It became a best-seller and remains to this day in print, his noble stoicism still providing inspiration.

Of the three explorers, Ernest Shackleton’s reputation is perhaps less tragic hero (not one man of the crew perished on his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, although the expedition failed to achieve its aims), more heroic survivor against the odds. Shackleton burnished his own reputation through sell-out talks at Philharmonic Hall and his published narrative South: The Endurance Expedition, which is still in print. His later death and burial on the distant island of South Georgia during his last expedition, helped mythologise his story.

There is no doubt that all three of these pioneers deserve their place in history. Theirs are inspirational stories of exceptional bravery and hardship. But perhaps those who have mastered the art of suffering, especially those who dedicated their lives – in Shackleton’s words – to ‘white warfare’, particularly capture the imagination. We see their stories as fables, myths with a powerful message of endurance and hope: despite the almighty forces of nature, humanity’s reasoning and endurance will prevail.