Shackleton’s voyage was remarkable, a real test of endurance. Seb’s adventure was the first reenactment using traditional equipment of part of Shackleton’s extraordinary voyage. The team recreated the voyage of the James Caird, the infamous escape attempt by Shackleton and a small team from Elephant Island to South Georgia in a lifeboat, including the crossing of South Georgia’s mountainous interior. Seb’s boat, dwarfed by the waves it sailed, completed that feat only ever previously achieved by Shackleton’s team 100 years ago.

Q. How did you get involved in this extraordinary project?

Not for a second did I think I would be one of the six guys on the boat. In the beginning my involvement was in an advisory role, to help reproduce a very authentic voyage. My research led to us having reindeer hide sleeping bags [Seb hands me a reindeer glove – it loses an extraordinary amount of hair as he passes it to me] and to building an exact replica of the boat Shackleton would have sailed in 1916. I was asked to join the boat team about halfway through the preparations; I said yes without hesitation. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Q.What inspired you to follow in Shackleton’s footsteps?

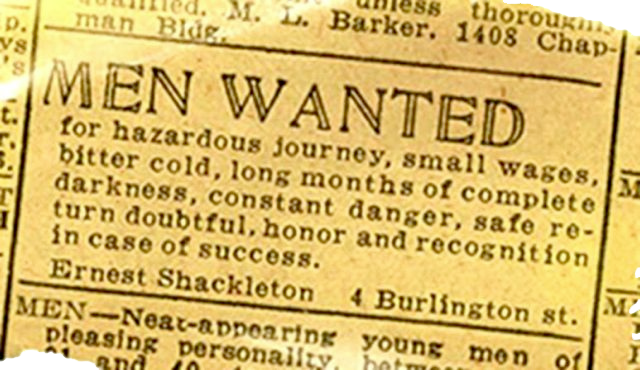

My inquisitiveness to explore history I think. It’s a tough question. Shackleton inspires me in many ways; there isn’t a single deed or action in isolation which I can pinpoint. Shackleton lived at a time when exploration required brave, loyal and optimistic people to venture into the unknown in order to fill in the blanks at the edge of the map. Organising, funding and equipping expeditions was no trivial thing in 1914; and to then select a crew and lead them effectively in a crisis situation, well, you have to be a very special person to do all that! Shackleton was able to manage the spiritual and physical survival of his men so effectively that he changed the way in which his companions saw the world for good, and that inspires me.

Q. Who built the boat, and was it the same as Shackleton would have used?

The International Boatbuilding Training College in Lowestoft built the hull, and I did a large part of the research in order to make sure we were building it as authentically as possible. The boat was named Alexandra Shackleton (‘AS’ for short) in honour of our patron, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s granddaughter. It was Tim Jarvis, the expedition leader, and Alexandra, who first developed plans for the boat and the expedition; my role was then to bring the expedition to life.

As we were building the AS, I often looked inside and thought how uncomfortable and cramped it looked, and it really was. During the build I couldn’t help thinking that this was a bad idea, so I spent a couple of mid-winter nights inside the bare hull. Despite being covered in frost the following morning, I was toasty warm in my reindeer skins. At that point I realised I was already immersing myself in the history, so I pressed on; I enjoyed it.

Several times when we were out on the sea during the expedition in rough weather, snow and ice accumulated on the sails and ropes. Down below in the living space, ten of the team lived in fairly squalid conditions, every so often getting a boot in the face, or picking reindeer hair out of the food. We stopped complaining after the third day because we knew it was going to be our way of life for at least two weeks. We were like sardines in a can. In terms of back up, we tried to keep things as equal with Shackleton as possible, but of course we didn’t want to die doing it, so although we used a lot of period equipment we did have modern emergency equipment and radios on board, and the presence of a support vessel, Australis. We joked that if a passing ship found us, they would probably have offered us assistance… and we would have had to politely decline! That would have been an interesting radio conversation with the Master of that ship.

Q. How long did it take you to build the boat?

It took about two years to build the boat and another six months to equip her ready for sea. At the time, it was a faithful replica given the extent of our knowledge and the limited budget. We made every effort to retain as many original features as possible including handmade flax sails and coarse manilla rigging ropes, we cooked on a Primus paraffin stove, and we navigated with sextant and compass. Since coming back from the expedition I have learnt a great deal more about the boat and in the end I decided to personally commission a second replica – the most accurate replica ever made. This new boat embodies every lesson learnt from the expedition, archival research and traditional boat building skills. She will be named ‘J.Caird’ (after the lifeboat Shackleton used himself) and in future she will be available for sailing to anyone with an interest in Shackleton history.

Q, How did you get the Alexandra Shackleton to your starting point?

The first part was pretty straightforward: we loaded it onto a cruise ship and got it delivered to King George Island in Antarctica. Some of the boat’s equipment was shipped later and sadly some of it ended up in the wrong country! I had to charter a tiny aeroplane and fly over to Patagonia to recover our essential equipment. This included four oars about five metres in length, and when I measured the aircraft’s cabin they didn’t fit, so I had to cut them in half!

After doing some glacial travel training on King George Island and preparing the boat for the long sea journey ahead, we towed the AS to Elephant Island. Once there, we turned the clock back and donned our period clothing. From that moment onward we were in 1916: no modern navigation aids, no weather forecasting and plenty of seasickness.

Q. It must have been very difficult; how many days into the voyage did you start to tire?

The sailing part was incredibly tough and after the first day losing sight of land wasn’t much fun. We spent most of the time either trying to sleep in wet clothes or helming the boat, and while we would have a joke here and there, the roller coaster waves stole most of our energy (anyone who says they don’t get seasick is probably not telling the truth). About half way through the voyage, water started seeping into the boat and that required constant bailing. Then there was the tendency of the reindeer-skin blankets to shed hair everywhere, including into the food – appalling conditions to some, but it’s only by experiencing this that you get close to understanding what it was like to be in the company of great men like Shackleton. I felt comforted in the knowledge that if Shackleton and his companions could pull through, so could we. Difficult, yes, but that made it all the more exciting, we were truly recreating what we had set out to do.

Q.Were there any particular challenges?

The greatest challenge was the Southern Ocean. Waves crashed around us all the time and on a couple of occasions we thought the boat would get swamped. Amazingly the AS was incredibly seaworthy and she pulled through everything the sea could throw at her. To this day I am still at a loss for an explanation as to how she survived – true testament to the boat builders of 1914.

[Seb later talked about his concern at not being able to prevent the boat flooding completely and when it came dangerously close to hitting rocks off South Georgia he worried that it might sink. The boat did, of cours,e complete the journey and is now on tour in the USA.]

Q. Any close encounters with wildlife?

That 800-mile stretch of the world’s most tempestuous sea is bleak and hard work, unlike the Antarctic peninsular further south. One afternoon whilst sailing, we heard the blow of a whale right next to the boat. Paul, our navigator leaned over the side and looked directly into the water, only to see the eye of an enormous whale looking back at him! It wasn’t until we reached South Georgia that we really got to see a huge amount of wildlife. At sea we saw majestic albatross swooping across the wave tops, penguins darting in and out of waves and seabirds laughing at our self-imposed tortuous journey. To be honest, there was never any shortage of wildlife – it was magnificent.

Q. You’ve trekked into the heartland of South Georgia, not many people can say they have done that. Shackleton crossed the island in 36 hours, how long did it take your team?

It took the team about 90 hours, and it was exhausting. Three of the six of us didn’t make it including myself – I succumbed to trench foot, due to being constantly wet during the boat journey. On arrival at South Georgia I decided to press on and support the team as far as the Murray Snowfield, a steep climb of about 3000 feet. We all got pinned down by a 80-knot blizzard that evening and our tent was ripped to shreds – such is the force of Mother Nature in those regions!

I don’t feel disappointment by withdrawing from the mountains stage because Shackleton would have done the same; he knew when to plant the flag and call it a day. Two team members continued in full period clothes across the island. It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life, to see those men, in period equipment walking across a glacier field. Shackleton is a legend and there is absolutely no doubting that ,and my respect for the Antarctic environment has increased ten-fold thanks to that experience. I shall return to complete my crossing.

Q. Would you do it again?

As I mentioned at the beginning of this chat, the reenactment expedition was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience a historical event which is never likely to be repeated, but I will continue to explore Antarctica for as long as I live. Shackleton’s right hand man, Frank Wild, said, “Once you have been to the white unknown, you can never escape the call of the little voices.” I know exactly what he meant by that.